In late February, the PACE Society, a long-standing pillar of support for sex workers in Vancouver, announced it was suspending services and programming and laying off most staff. For more than 30 years, PACE has provided peer support, counselling and basic services using a “by, for and with” sex workers approach.

Now, amid a funding crisis that has led to layoffs of mostly staff with current or former experience of sex work, the future of vital support services for sex workers in Vancouver is uncertain.

PACE’s announcement was another heavy loss following a string of closures and service reductions at organizations serving sex workers and other marginalized women in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

February also marked the closure of the WISH Drop-in Centre. The centre provided essential lifeline for street-based sex workers in the Downtown Eastside, offering overnight respite and critical access to resources for over four decades.

While PACE and WISH have described their closures as temporary, their eventual reopening remains uncertain. Both organizations intend to resume services with the renewal of the funding cycle in April 2025. In the meantime, sex workers face an urgent and growing void of essential support services and community spaces.

Making sex workers more vulnerable

As collaborators on the AESHA Project (An Evaluation of Sex Workers’ Health Access), we have worked in partnership with sex workers and community organizations to document how criminalization, policing and structural inequities impact sex workers’ health and safety.

For over 14 years, the AESHA Project, based at the University of British Columbia, has highlighted the crucial role of community services in supporting sex workers’ health, safety and well-being and how a lack of funding undermines sex workers’ access to these vital services.

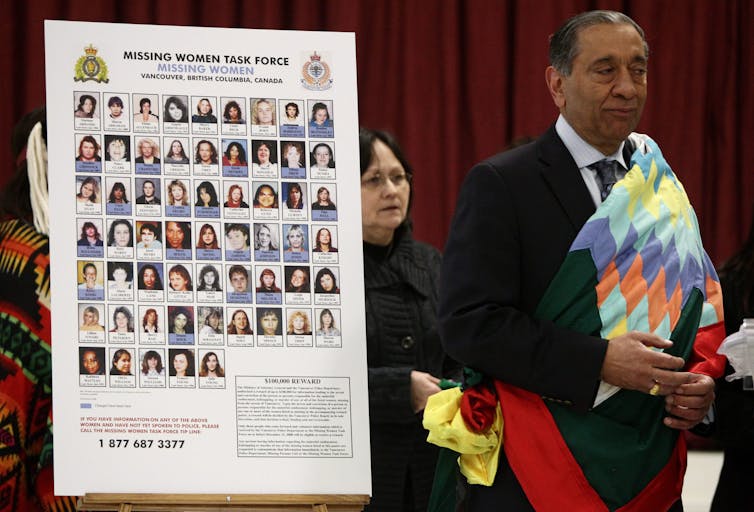

The loss of safe spaces for sex workers, even temporarily, carries profound and far-reaching consequences. These impacts were thoroughly documented in the findings of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, led by former B.C. attorney general Wally Oppal. The inquiry examined systemic failures that contributed to the targeted violence and murders of sex workers in Vancouver.

Among the commission’s key recommendations was the urgent need to enhance protections and expand access to critical supports for sex workers, recognizing that such services are fundamental to their safety and well-being.

For years, front-line organizations such as WISH and PACE have been instrumental in advancing this mandate, providing basic necessities like hot meals and safe overnight spaces, as well as trauma-informed counselling, peer support networks and opportunities for community connection. The abrupt closure of these spaces severs support networks for sex workers.

Chronic under-funding

Such organizations are vital, and sex workers deserve to feel like these spaces matter and are worth keeping open. However, funding for community-led, rights-based approaches to sex work services has historically been limited in Canada. Federal governments have prioritized prohibitionist approaches and “exit programs” that do not meet community needs.

Vancouver-based sex work services are not alone in experiencing funding shortfalls and closures. On March 7, SafeSpace London issued an urgent call for donations following the loss of city funding. This dynamic is also visible in Vancouver, where the closure of PACE and other similar organizations is occurring within the context of a broader “revitalization” agenda, which aims to prioritize development over community infrastructure.

A leaked draft memo from October 2024 revealed Vancouver Mayor Ken Sim’s plan for reshaping the Downtown Eastside. Among these plans is an effort to expedite private development approvals, notably through the use of spot rezoning — a tool that allows municipal authorities to rezone individual outside the city’s established planning frameworks.

The memo also outlines the Sim’s intention to conduct a comprehensive review of local non-profit organizations and to actively “track their funding envelope.” While framed as a step toward increased accountability, research highlights that heightened scrutiny of chronically under-funded community organizations often leads to greater instability and compromises service delivery.

Non-profits are in crisis, but this cannot be solved by increased surveillance and funding cuts. Community organizers have critically examined the potential consequences of this development-driven approach, raising concerns that it will accelerate gentrification and undermine the availability of essential community services.

Community organizations, often relied upon to fill the gaps left by government disinvestment, often face chronic funding shortages. Despite providing essential services, many are forced into cycles of short-term, unstable funding that limit their ability to plan for the long term or advocate for systemic change.

This precarious situation is not incidental. It reflects a broader shift in recent decades of governments offloading responsibility for social welfare onto under-funded non-profits while maintaining the illusion of support with fragmented funding schemes.

The closure of critical services is not a sign of individual organizational failure. Rather, it is a direct consequence of a system that prioritizes investments in policing and property development over sustained investment in community well-being and support for the most marginalized residents of Vancouver.

Organizations that provide critical support to sex workers need stability and self-determination to cultivate meaningful, community-led approaches that meet immediate needs and work toward long-term change.